Contents

- Introduction

- Prelude – Understanding Mental Representations

- The Elements of Deliberate Practice

- 1: A Highly Developed Field

- 2: Target Specific Sub-Skills

- 3: Clear and Immediate Feedback

- 4: Focused Practice

- A Brief Interlude About the Dangers of Over-Efforting

- 5: Get Out of Your Comfort Zone

- 6: Continued Engagement

- A TL;DR Summary of Deliberate Practice

Introduction

Most meditation instructions that you’ll find go something like this:

- Place your attention on the object of meditation (usually the sensations of breathing at the nostrils) and keep it there.

- If you notice that your mind has wandered, bring your attention back to the object of meditation – and don’t beat yourself up about it.

You’ll also get some descriptions of what the experience of meditation can be like if you keep doing it, some explanation of Buddhist philosophy/psychology, some funny or heartwarming anecdotes, and perhaps some impressive results from the recent scientific study of mindfulness and meditation practice.

This material can be profoundly wise, beautifully written, greatly inspiring, and express important truths. Yet in terms of actual, practical meditation instructions, there’s rarely much detail beyond those minimally outlined above.

Unfortunately, these instructions are severely limited. They are the equivalent of trying to learn chess by just moving some pieces around the board, seeing what happens, vaguely trying to checkmate the enemy king, and not beating yourself up if you lose. Well and good for beginners learning how the pieces move, but it will take one a hundred lifetimes to master chess strategy this way.

If merely spending a lot of time on something was enough to master it, all of us should be speed-readers and speed-typists. Yet, even though most of us spend a lot of time every day typing and reading, there is a specific style of practice that separates us from the extraordinary performance of speed-readers and speed-typists, who have learned to do their thing many times faster than the average person.

What’s the best way to get good at a skill? This is the question that researcher Anders Ericsson (see his excellent book Peak for more details about his fascinating research) has devoted his career to answering.

A clear picture has been revealed by his study of the best performers in many varied fields of expertise. Whether they are chess players, marathon runners, fighter pilots, doctors, swimmers, or spelling bee champions, experts are differentiated from amateurs by one thing: how they practice. Regardless of the skill in question, there is an extraordinary overlap in how the very best have used their practice time to become so good.

This style of hyper-effective training is called deliberate practice, and it applies just as well to meditation as any other skill. Apart from saving you literally thousands of hours of ineffective practice time, a good understanding of its principles will allow you to see real, fast, fun, and extremely encouraging progress in your practice.

This information is an extraordinary gift. A clear scientific understanding of how to build expertise has not been available for the whole of human history up until now. Those extraordinary musicians, Olympians, and other heroic experts who came before us were merely those vanishing minority who, by chance or good intuition, kept to the principles of deliberate practice. These principles are now well understood and available for our use, and this blog is intended to give you an applicable understanding of them.

Quick note: this blog mostly focuses on concentration (shamatha) meditation, rather than insight (vipassana), loving-kindness, or other types of meditation. The principles apply to pretty much all of them, yet for the sake of simplicity, my focus is on the former.

PRELUDE – UNDERSTANDING MENTAL REPRESENTATIONS

“What sets expert practitioners apart is the quality and quantity of their mental representations” – Anders Ericsson

Try to memorise this list of letter groups:

AFB IUS ACI AGO OGL ENAS

Alright, now try this one:

FBI USA CIA GOOGLE NASA

Easier? That’s because there’s already a lot of stored information in your brain that gets activated by these letter groups. In other words, you already have strong “mental representations” of them. Developing more and better mental representations is the key change that results from deliberate practice, so it’s key to understand what mental representations are and why they play such a central role.

When you look at the letters “FBI”, your brain activates networks that connect it to the words “Federal Bureau of Investigation”, and probably images of uniformed people in TV shows pointing guns and shouting “Freeze, FBI!”.

The obvious difference between looking at random strings of letters and looking at well-known acronyms is similar to the difference that chess masters experience between looking at random arrangements of chess pieces and looking at meaningful chess positions.

When you hear “FBI”, the individual letters barely register in consciousness – rather, you are aware of the higher level concept. Just so, when chess masters see a chess position, their brains “chunk” the positions of individual pieces into higher-level concepts like “active white bishop”, “undefended squares”, “compromised kingside pawn structure”, and so on. These are the kinds of mental representations that chess experts have had to master, because they give one insight into subtle strengths and weaknesses of a chess position which would be invisible to anybody without such representations.

This is why, as some fascinating experiments have demonstrated, chess masters can memorise the positions of every piece on the board within a few seconds if it is a realistic chess position, but when the board is arranged randomly, their ability to memorise it is the same as an average person. If the pieces are placed randomly, the higher level concepts don’t apply; the board doesn’t “mean” anything – just as when letters are arranged randomly, they are hard to memorise because they don’t mean anything.

Sports too, and even highly repetitive endurance sports, which one may expect to require little beyond a well-trained body, all have their own highly developed mental representations. Marathon runners have extremely precise representations of the exact movements of a perfectly efficient stride, what kind of interoceptive feedback they should be getting when they are pacing themselves just right, and so on. These representations allow them to perform much better than a regular person, to whom the body sensations associated with one kind of stride aren’t meaningfully distinct from another, and to whom the sensations associated with pacing oneself slightly incorrectly are just body sensations – they do not “mean” anything. I myself am not very adept at reading such signals, and this is why, when I went out for a run the other day for the first time in longer than I would care to admit, I estimated that I would be able to maintain the optimistic pace I started off at for much longer than I, in fact, could.

Marathon runners, chess players, musicians, rock climbers, surgeons, and artists all require a unique set of mental representations to perform their skills well. It should be no surprise that the same is true for meditators, then.

The key change that results from effective practice is an increasing quality and quantity of mental representations. So, what are the elements of practice that best achieve this?

THE ELEMENTS OF DELIBERATE PRACTICE

1. A HIGHLY DEVELOPED FIELD

In the 1920s, the chess grandmaster José Capablanca worried that knowledge of the game of chess was close to becoming so complete that grandmasters would be able to memorise all the strongest lines of play and world class matches would always result in a tie. To combat this, he created a new form of chess with a larger board and new types of pieces.

This “Capablanca chess” is an example of a skill to which one would not have been able to apply the principles of deliberate practice, because it was not developed enough as a field of knowledge. The new pieces and larger board in Capablanca chess would lead to positions that nobody had seen before, and interact with the other pieces on the board in ways that nobody would be able to foresee. It would take many years of experimentation to hit upon the right mental representations to make sense of these. If you wanted to become an excellent player of regular chess, in contrast, there were detailed training methods already well-established to impart to you directly the highly developed mental representations associated with it.

Having an established field with fleshed out mental representations and the training methods to impart them effectively are an essential prerequisite for deliberate practice. Such deliberate training methods can directly develop mental representations which may have taken lifetimes to figure out alone.

A field also needs to have an objective measure for skill. Wine tasting is an example of a field with little objective measure of skill – wine experts, when blind taste tested, disagree with each other, and will even contradict their own earlier ratings on measures of quality. Given this lack of objective criteria for progress, one cannot get meaningful feedback – and as we shall see this is another crucial requirement for effective practice.

| A Highly Developed Field In Practice: The Mind Illuminated These “In Practice” boxes will give examples to show how the principles of effective practice apply to meditation. The examples will be drawn from the book The Mind Illuminated: A Complete Meditation Guide Integrating Buddhist Wisdom and Brain Science, by Dr. John Yates (AKA Culadasa). This book is an unmatched resource for learning concentration (samatha) meditation, and details the mental representations to work on at each level of skill along the path of concentration, and which practices to target them effectively. I’ll move through the first six of the ten stages of concentration covered in the book, giving an example of how a principle of effective practice is put into practice at each stage. However, these examples are merely that, and are no substitute for the book itself, which covers much more, and in more detail. The first stage of practice from The Mind Illuminated is to establish a regular practice, and getting to grips with the basic instructions of mindfulness of breathing meditation. I’m going to assume that readers of this blog are already familiar with these steps, and skip describing this stage. |

2. TARGET SPECIFIC SUB-SKILLS

To develop a skill effectively, you must first break it down into smaller and more specific sub-skills, and then practice in ways that target these sub-skills individually. This allows you to develop from more foundational to more advanced mental representations much more rapidly than trying to practice all of them at once.

When you start learning chess, you need to learn how the pieces move before moving onto beginner-level puzzles. It will take you a lot longer to progress beyond beginner’s puzzles if you’re trying to work out how the pieces move at the same time. Similarly, it will take you a lot longer to progress beyond intermediate level puzzles if you’re trying to figure out the concepts taught by beginner level puzzles at the same time, and so on. If you just dived right in and started playing a real opponent, you’d effectively be trying to learn all these things—which is to say build all these mental representations—at once. This is why, as chess coaches will tell you and actual research demonstrates, just playing lots of chess is not an effective way to get better at chess. It simply isn’t focused enough. Skill at chess correlates much better with time spent studying specific strategies and practicing specific tactics than time spent playing actual games of chess.

You can’t build every level of a house of cards at once. You have to work from the bottom up, and exactly the same is true of skill development in any domain – including meditation.

“If I need to work on my body position at the end of my races, then I would push myself in practice to the point of exhaustion then work on my body position when exhausted.”

This is American Olympic swimmer Natalie Coughlin, and is a perfect example of working on specific sub-skills. She had clearly recognised that the biggest opportunity to improve her technique is when it was degrading near the end of a race, and so worked on how to improve her body positioning as effectively as possible when she was tired.

So it’s essential, first of all, to get clear on which are the sub-skills/mental representations that you need to work on, either because they are foundational, or because they are simply your weak points. Then the question is how to practice in a way that targets one or two of your weakest sub-skills very deliberately and specifically. This is why it is so helpful to have a teacher to help you to identify which mental representations you are lacking, and which practices to use to fill those gaps.

It’s so easy to sit down to meditate without setting clear intentions for which sub-skills to target. It takes work to get deliberate and to keep track of which mental representations are your weak points. But the effort put into doing so will be rewarded with a vastly superior rate of progress.

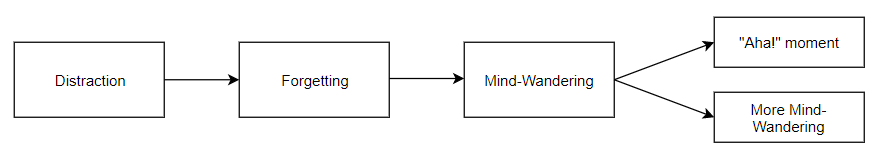

| Target Specific Sub-Skills In Practice: Stage 2 When you sit to meditate and start paying attention to your breath, it will not take long for a distraction to arise and capture your attention. The distraction may be a slight itch that barely causes a flicker in your attention, or it could be a juicy fantasy that captures your attention so entirely that you forget the meditation object altogether. If it’s the latter, mind-wandering will soon follow; the thought leads to another thought and so on. After a little while you will suddenly realise “Aha! I’m mind wandering but I had intended to meditate”. Here’s that progression again:  For the beginner, most of the time spent on the meditation cushion will be occupied by mind-wandering. Therefore, the appropriate sub-skill to target at when you first begin the practice of meditation is to cultivate the tendency to have an “Aha!” moment. What is your usual reaction when you notice that you’ve been mind-wandering in meditation? If you’re like most people, it is to jerk your attention back to the breath and clamp it down with a huff of exasperation. But reward is a better teacher than punishment – especially in meditation, where peace, contentment, and joy are so supportive of stable attention. You can develop the propensity to notice and correct for mind-wandering more quickly and more agreeably by reinforcing these “Aha” moments with pleasure and relaxation. When you notice that you’ve been mind wandering, relax your face and your whole body; fully savour any pleasant sensations that come from relaxing, as well as the experience of greater awareness now that you are once again mindful of what your mind is doing. Congratulate yourself; allow yourself to feel grateful for having noticed your wandering mind. Positively reinforcing this “Aha!” moment will help you to catch mind wandering faster and more frequently. Soon, you will be able to notice mind wandering almost as soon as it begins; the moment of forgetting the meditation object will become a cue for an “Aha!” moment. This will speed up your progress immensely, and you will feel not tense and frustrated, but peaceful and joyful upon noticing. The other sub-skill beginner meditators can be working on at the same time, when they are not mind-wandering, is the ability to maintain attention on the sensations of the breath for longer and longer periods of time. This is done by essentially playing a game to notice details about the sensations of the breath. What actual sensations are present? What does it feel like, really, when you breathe? It’s challenging to keep attention on this for more than a few seconds at first, so it helps a lot to pick a particular part of the breath – such as the start of the in-breath and the start of the out-breath – to notice their accompanying sensations. It also helps to count each breath, for example by mentally placing a count after the out-breath, and starting again after every 10 breaths.  1. Start of the in-breath: paying attention to what breath sensations are present. 2. Start of the out-breath: same thing. 3. Placing a mental count to help keep attention from wandering. Again, peace and joy are also an inestimably helpful part of learning to keep attention on something – so enjoy, savour, and relish, revel in, and feel grateful for whatever pleasant sensations of the breath you can, even if they are very small, simple pleasures. As you get better at this game, you will enjoy meditation more, your attention will stay on the breathing for longer, you will mind-wander less frequently. |

3. CLEAR AND IMMEDIATE FEEDBACK

Let’s say you want to learn how to bake a soufflé – this is quite challenging, and involves getting many steps just right. However, you’ve read the above section about specific sub-goals and you’ve figured out what your weakness is: you don’t really know what consistency the mixture should be. By figuring that out you’ve already saved yourself a crapload of time. Great work!

You make your best guess, and fifteen minutes later you pull out of the oven a flaccid and inedible abomination that looks like it belongs in a David Cronenberg movie. This is delayed, non-specific feedback; by the time you take it out of the oven, you’ve probably already forgotten precisely what the mixture looked and felt like. Also, why was it wrong? Was it not thick enough, not fluffy enough, too thick, or something else? It could still take a lot of Cronenberg soufflés before you crack it.

Imagine how much faster you’d be able to develop your mental representations if you had a chef present to give you immediate feedback on why your mixing technique is wrong and how to get it right.

Feedback is the only intermediary between doing something and improving at it. Without feedback, “practice” is just doing something lots of times – which, contrary to common opinion, will not lead to improvement.

If merely performing an action were enough to improve, one would expect that doctors would become more skilled as they become more experienced. Yet, out of 62 studies included in an extensive review by Harvard Medical School into the performance of doctors over time, exactly the opposite was true. Almost all the studies showed that performance decreased over time, and only two found that doctors actually got better with experience.

Why? Because they were not receiving feedback. If a radiologist finds out that she got a mammogram reading wrong at all, by the time she finds out she will in all likelihood have forgotten all about what led her to make the decision she made. This has sparked programmes that use databases of verified mammogram results for radiologists to practice diagnosing. These databases can immediately give feedback on whether the diagnosis was correct, and so help doctors to identify where their mental representations are incorrect or incomplete.

For any skill we are trying to learn, we too should utilise or devise new ways to get immediate feedback from our efforts. In meditation, this is often highly non-intuitive because at first it involves taking a step back from paying attention to the breath (or however we happen to be meditating) to check how well we are meeting the goals of the sub-skill/s we are currently working on. We must learn to develop an awareness for sources of useful feedback. We’ll look more closely at this process in the next ‘In Practice’ section.

It doesn’t feel right to be actively looking for evidence of what we are doing imperfectly. It is natural to want to feel like you have learned a skill, and now you are simply performing it. But just like the mammogram reading doctors from our earlier example, simply doing something repeatedly will not help you get better at it. To improve, one must modulate one’s efforts in response to feedback—the more immediate the better—and this means staying attuned to it.

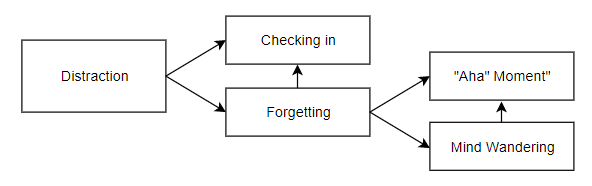

| Clear and Immediate Feedback In Practice: Stage 3 So, now you mind-wander less often in your meditations, and when you do, you usually catch it quickly. This is fabulous progress. The next step is to overcome forgetting about the meditation object, which happens when a distraction arises and captures your attention so strongly that, well, you forget about the meditation object. In this instance, the sub-skill to target would be the ability to notice distractions before they cause you to forget the meditation object. In other words, you need to develop a degree of background awareness of what your mind is doing. When you first start learning to drive, your attention is so fully occupied with coordinating the gears, the clutch, and the other pedals that you hardly have any mental space left over to pay attention to what’s actually happening on the road. When these things become second nature, you then need to learn to keep an eye out for road signs and so on at the same time. In the same way, now that paying attention to the breath has become a little easier for you, and you are now spending a higher proportion of your meditation session actually doing so rather than mind-wandering, you now need to start checking in on what your mind is getting up to, so that you don’t do the meditative equivalent of missing your turn: getting carried away by a distraction that you didn’t notice. So, what’s the clear and immediate feedback to look for at this level of skill? You will develop your awareness of distractions by “checking in” every half-dozen breaths or so, on whether there are any distractions present. You’ll be paying attention to the breath, decide to “check in”, and take your attention away from the breath for a brief moment to see if any distractions are present in the background. Your check-in may discover no distractions present at all – which is great! You can just go straight back to meditating. However you may be surprised to find, more often than not, that even while you were paying attention to the breath, there was also a train of thought going through your head at the same time.  This moment of successfully catching a distraction before it has displaced your attention entirely from the breath is the positive feedback you want. If you notice that you have forgotten the meditation object or begun mind-wandering, that means you didn’t catch the distraction soon enough. This is the ‘negative’ feedback – it may indicate that you went too long without checking in on your mind. When this happens, you can simply relax and savour, just the same as you did after the “Aha!” moment from before, and then re-clarify your intention to pay attention to the breath and to check in – perhaps a little more frequently than before. At first, this is a bit of a pain in the arse to keep doing – it can be distracting and disruptive. As Abayakara puts it in his blog about checking in: “Checking in is the process of periodically stopping the meditation and looking to see what was just happening. At first this can be like driving a car, and you stop the car, get out, and look around. Very disruptive. But as you do it more and more, you start to be able to treat it more like glancing in the rear-view mirror—something you do every so often, sort of automatically, that doesn’t take a lot of effort and doesn’t feel like a major interruption—just a little blip.” Soon enough you will even begin to find that your mind starts catching distractions before you even consciously intended to check in at all- but this brings us to the next stage. The second piece of feedback simply corresponds to continuing to develop your ability to pay attention to the breath, by looking for more detail in each part of the breath cycle. The feedback is simply how much detail you are able to find, and how continuously you are able to find it. If you are using counting the breath, then the count is another piece of feedback to look for; if you notice that you aren’t counting anymore, have lost count, or have absent-mindedly continued to count above 10 (or whatever number you’re using before you go back to one), this is an indication that your attention has been captured, or that you’re dozing off. |

4. FOCUSED PRACTICE

“My best attribute is my ability to be highly focused for long periods of time.”

– Natalie Coughlin, 12-time Olympic Medalist

One’s sensitivity to feedback, as we have just seen, determines the rate at which one is able to improve. Somebody who is fully mentally engaged with their task has a massively increased capacity to detect and respond to feedback, and thus their rate of progress will be commensurately increased.

Let’s use the example again of American swimmer Natalie Coughlin, who won a total of 12 Olympic medals over her career. Early in her career she spent most of her time in the water daydreaming to distract herself from the tiring training. But she describes that at a certain point, her coaches helped her to realise that correct technique doesn’t simply happen by itself, and the daydreaming had the enormous opportunity cost of preventing her from actually correcting the imperfections in her technique. After that, she began to bring full attention to the mental representations of her stroke – developing a feel for precisely how a perfect stroke feels.

Daniel Chambliss carried out an extended study of excellence in Olympic swimmers and concluded that the key was staying engaged with the process of improving every detail of performance until “excellence in every detail becomes a firmly ingrained habit”. This is by no means unique to swimming. The development of all skills requires the presence of mind, moment to moment, to attend to what the feedback is telling you, and adjust your efforts accordingly. Meditation is, of course, no exception.

Sustaining mental engagement is demanding work! What our brains want to do is learn to perform a task adequately enough, and then to just keep doing that thing on autopilot. This saves a lot of energy – it requires a fair amount of extra processing power to stay attuned to the minutiae of the task you’re performing. However, it is necessary to do so if you want to improve. If you are practicing on auto-pilot, you will be reinforcing bad habits.

| A BRIEF INTERLUDE ABOUT THE DANGERS OF OVER-EFFORTING This stuff can be highly appealing to those who have a tendency to use too much effort and striving in meditation practice. Keep in mind that even the best meditation practice in the world does not require a lot of effort. A high degree of mental engagement does not mean Herculean effort. It doesn’t even mean a lot of effort! The difference is that over-effort tries to force the mind to behave in a certain way, whereas mental engagement merely ensures that skilful intentions are kept front of mind. This is the difference between lovingly and patiently training a dog, and just tugging harder and harder on its leash. Gentle but persistent intentions are all you need. See if you can cut the effort that you’re using in half. Then see if you can cut it in half again. If you’re like me, this will actually make your practice more effective, since over-efforting creates so much tension in the mind and body that does nothing but gum up the works. All you need to do is hold the right kinds of intentions, and refresh them when necessary, with relaxed diligence. If you think you might have a tendency towards over-efforting, then you may find it a highly useful complement to your practice to do some loving-kindness meditation, or ‘just sitting’ and even ‘do-nothing’ types of meditation as well. |

| Focused Practice In Practice: Stage 4 Okay, so now you’ve been practicing with “checking in” for a while and distractions still arise, of course, but for most of the time in most of your sits, you can catch them before they cause you to forget the breath entirely. The next step is to cultivate the ability to notice distractions without needing to check in. Checking in, to continue the driving analogy from the last section, is like intentionally looking out for traffic signs when you’re driving, so you don’t miss your turn; in meditation these signs say “you have now reached Distraction Road – keep straight on for Forgetting Street and Mind-Wandering Boulevard, or turn here to get back to Meditation Lane.” Of course, when you drive in real life, you don’t need to be constantly keeping in mind to look for traffic signs; you don’t need to do check-ins for them because when they pop into your field of view, you immediately notice them. This is how we want to be able to feel about distractions: as soon as they pop up, we don’t need to look for them, we just immediately know that they’re there. Unfortunately, traffic signs are designed to be noticeable, and distractions are most certainly not. Paying close attention to the breath, if you’ll forgive me stretching this metaphor to breaking point, is like driving whilst looking through a telescope: you can see a lot of detail ahead of you, but lose all peripheral vision. Before you know it, some distraction that you didn’t notice approach has cut you off and is now obstructing the view of the telescope. You must develop a kind of radar to notice distractions coming so you can avoid them before they cause you to forget the breath. Checking in was the beginning of cultivating this radar, but it was only ‘on’ when you were specifically using attention to look for distractions. Now you’re ready to develop that radar so that it’s on all the time. You’ll probably notice that, after you check in and then return your attention to the breath, there’s still some residual awareness of the activities of your mind. Even though your attention goes back to the meditation object, you are able to notice distractions, for a few seconds at least, even without intentionally looking for them. This heightened awareness is the state of mind we want to get a feel for and extend in this stage. If you know you’re going to have a baby soon, even though you’re not looking for them, you start seeing prams and babies everywhere that you never paid attention to before. In a similar sort of way, when you repeatedly check in for distractions, your mind learns that you want to notice them, and will develop an awareness of these distractions that wasn’t there before. This awareness is different from paying attention to things. There are many things you are currently aware of that you aren’t paying attention to – you’re aware of what room you’re in, the position of your body, possibly the music you are listening to. You don’t need to keep paying attention to check what room you are in, but you are nevertheless aware of it. This state of mind feels a little like taking a step back from the meditation object, so that you are still paying attention to it, but there is some space around it, in which you can take in the other activities of your mind. It’s like carrying a full cup across a busy room – you are paying attention to the cup, but you are still using peripheral vision – you needn’t be fully aware of what everybody around you is doing, who they are, and what they’re wearing, but just aware enough to avoid walking into them. Sustaining both sufficient attention on the breath, and sufficient awareness of peripheral mental activity, is a difficult balance to hold. Like all these techniques, it requires focused practice. |

| Awareness of peripheral mental activities | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficient | Sufficient | ||

| Attention to the breath sensations | Insufficient | Drifting/dozing off/mind wandering | Catching distractions, but non-distinct focus on the breath – thus not developing concentration & not making progress |

| Sufficient | Hyper-focus, highly susceptible to distractions or sleepiness | Clear focus on breath, also catching distractions as they arise. | |

| It is useful to continue to use checking in, but you can begin to spend less time and effort checking in until you are just refreshing your awareness ‘radar’ with a light flick of intention. At first, you may want to refresh this radar as often as every breath or two. You will get a feel for this soon enough, and it won’t take long to become an automatic part of your meditation, which requires refreshing less and less often. When this ‘radar’ of awareness is active, you will notice thoughts and other distractions arising before they carry you away from the breath. You will then be able to lightly re-clarify your intention to keep attention on the breath. This is one of the tools of full engagement that all expert practitioners must learn to bring to their craft: quick, frequent checks to refresh intentions, which allow one to monitor performance and make corrections until correct technique becomes second nature. It is not enough to just half-heartedly try to follow the breathing and occasionally make sure that you aren’t distracted. You need to be paying close attention to your mental state – enough to make fine adjustments from minute to minute, and moment to moment. Don’t allow yourself to develop bad habits as you are learning this balance. Natalie Coughlin became an Olympic level swimmer by focusing on getting every detail of each stroke right, and practicing it until she had a ‘feel’ for the perfect stroke. Meditators can do the same thing; develop a ‘feel’ for the quality of mind to bring to each breath cycle. |

5. GET OUT OF YOUR COMFORT ZONE

“The hallmark of deliberate practice is that you are trying to do something that you cannot do” – Anders Ericsson

If you’re trying to do something that you can already reliably do, you may be getting a little better at it, but you’re probably just maintaining a plateau. You will improve much more if you are trying to do something that you can’t already do.

Our bodies – and that includes our brains – are really good at maintaining homeostasis. If your muscles are working hard to lift a weight, they get bigger so they don’t struggle as much next time. Once they can lift the weight without strain, they stop getting bigger.

If you’re using your brain to do something difficult, the axons connecting the brain cells required for the task will get insulated with myelin sheaths, which increases the speed of nerve impulses by up to 10 times. Your neurons will produce more calcium channels to reduce their activation threshold, more proteins to produce more neurotransmitters, and even surrounding neurons will be co-opted to contribute to the task. This will make it easier to perform the same mental task next time. But, just like muscles, your mental capacities will only get stronger if they have been put under strain. If you’re using your brain to do something that it already finds pretty easy to do, you’ll no longer be improving. Working within your comfort zone makes no changes.

It’s when you are trying to do something that you can’t reliably do already that feedback will give you the most information on where your mental representations are falling short. This is generally not the most pleasant experience. In fact, studies into musical expertise reveal that virtuosos unanimously report that making improvements is hard work; so much so that it is not generally enjoyable. Amongst the most skilled musicians, there were no prodigies playing in their rooms all day for the sheer fun of it.

Playing just for fun doesn’t yield improvements, because one can only have fun inside one’s comfort zone, and deliberate practice requires getting out of it. Now, I believe that the cultivation of joy, and learning to relate to one’s experience and goals with self-compassion, kindness, acceptance, and open-heartedness are crucial sub-skills for meditators, and not so much for violinists, so it may be reasonable to expect a skilled meditator to enjoy practice more than an equivalently talented violinist. However, these are genuinely skills, which will require trial and error, frustration, difficulty, patience, fine-tuning, and ingenuity to develop, and so the point remains: if you want to zone out and just enjoy not doing much of anything for an hour, that’s perfectly fine, but you will not be getting better at meditating.

Meditation is a complex skill, composed of a number of different sub-skills (and sub-sub-skills), and not all of these will develop at the same rate. A plateau in improvement will often indicate that a shortcoming in one of these sub-skills is acting as a limiting factor. Pushing yourself a little harder than usual may help you see what “breaks first”, at which point you can find a practice to work on that sub-skill. For example, if you try bringing more attentional clarity to the meditation object, you may notice that you start to feel sleepy. This is a good indication that dullness may be holding you back, and so you may experiment with focusing on and overcoming dullness for a little while to see if it helps (see The Mind Illuminated for a full definition and discussion of overcoming dullness).

With all this said about the virtues of going outside your comfort zone, if you try to learn boxing by getting into the ring with the heavyweight champion, it won’t matter whether you manage to improve your footwork a bit; you’re still going to be beaten into jam. The same goes with jumping straight from beginner to expert chess puzzles, or to start weightlifting by trying to deadlift 300kg. Even if you do get a little better, the challenge is so great that you will still fail to get positive feedback from which to learn. So the trick is to be practicing in that Goldilocks range of challenges that are only just within the range of your ability, such that only your full mental engagement with the task will be rewarded with positive feedback.

| Get Out of Your Comfort Zone In Practice: Stage 5 So now you’re able to notice potential distractions as they arise, and before they distract you from the breath. However, your attention is probably not as clear and vivid as it could be. This is what we will address next: increasing the clarity of attention without subtracting from your ability to catch distractions. This is tricky at first, because if you make your attention hypervivid and focus in on the meditation object as much as possible, you will probably find that it makes you more prone to distractions or dullness. This is due to the fading of peripheral awareness. At this stage, you will work on sustaining a high level of awareness and a vivid attention on the meditation object at the same time. It’s possible to do this just by continuing to focus on the breath sensations at the nose and look for more and more detail. However, it’s faster and more enjoyable to use a new body scanning technique at this stage. The technique, in brief, is to switch your attention from the sensations of the breath at the nose to another body part, and look for the subtle sensations that correspond to the movement of the breath in that body part, whilst—crucially—not allowing awareness of the rest of your body or of mental states to fade. After a little bit of time spent doing this, bring your attention back to the sensations of the breath at the nose, and see if the clarity of your attention has increased; you’ll be able to tell because the sensations at the nostrils will feel more vivid and ‘high-res’. See if you can sustain this high-resolution attention at the nose, and if it starts to fade, pick another body part and start the technique again. This technique works because it challenges you to look for very subtle sensations. Looking for breathing sensations in your nostrils has become second nature to you at this point, and it has probably become easy to slip into your comfort zone. Searching for the breath sensations in your shoulders, or your pelvis, or even your feet, on the other hand, requires much more careful attention – it pushes you outside your comfort zone. It doesn’t really matter whether or not you can actually find clear breath sensations in every body part (though if you keep this up you probably will); what matters is that this exercise demands that you bring your full powers of attention to bear on the task. Sustaining full attention, and at the same time ensuring that awareness doesn’t fade (using the skills you have already learned from previous stages), is a difficult task at first. You are likely to find that this exercise tires you out very quickly. That’s good! Don’t wear yourself out so much that you can’t keep meditating, of course, but try to push your limits a little each time you sit. Whatever circuits in your brain are responsible for attentional clarity will be getting a workout, and will be getting whatever the neural equivalent of jacked is. You will find that you are eventually able to maintain this state of vibrant attention for a long time without losing the power of awareness to notice distractions or dullness creeping in. As somebody who has wasted a lot of time by sticking with a practice long after I could have moved on to more advanced ones, my heartfelt advice is to be bold in moving on to more advanced practices. Don’t stagnate. If what you’re doing isn’t working, try something different. If you are trying to do something that you can already do fairly reliably, challenge yourself in new ways until you are trying to do something that you can’t. Be flexible, don’t be ashamed of switching to working on more fundamental skills when you need to, and take pleasure in experimenting with the edge of your comfort zone. |

6. CONTINUED ENGAGEMENT

Well, that’s pretty much all the elements of deliberate practice. The only one that’s left is to keep practicing, which is easier said than done.

In studies of experts, all high-level practitioners had a strong motivation to keep practicing. That may have been external pressure from parents or coaches (not recommended), a highly competitive mindset (also not recommended), or simply the love of perfecting a rewarding art, and the joy of seeing improvements (recommended).

The benefits of practicing for longer periods of time were also borne out in the data. In every field, the very best practitioners had spent tremendous periods of time perfecting their art. Comparing the average lifetime hours devoted to solitary practice by good, better, and world-class violin students by the time they were 18 yielded the following numbers:

Good: 3,420 hours

Better: 5,301 hours

Best: 7,410 hours

There were no prodigies who were able to get as good on less practice time. To master an art, it is necessary to put in many hours of deliberate work.

It’s hard to keep practicing from month to month if you’re just sitting there doing the same thing. It’s much easier when you’re engaged in a fascinating and dynamic challenge, where you are continuously unlocking greater levels of your potential and where the progress made is visible and encouraging.

| Continued Engagement in Practice: Stage 6 You are now able to focus on the meditation object with highly vivid attention, and yet your awareness of your background mental activity is still so sensitive that it can catch distractions before they carry your attention away completely, and notice when your mental energy is falling before you become dull. However, there are still subtle distractions that your attention alternates with briefly. These may be images, thoughts, emotions, body sensations, and so on, that quickly arise and pass away in your mind. While they do not pull your attention completely away from the meditation object like grosser distractions, they still tug on it somewhat, and so the next step is to overcome even these. This is done with a variation on the body scan practice. Instead of placing attention on the breath sensations in one body part, you gradually expand the scope of your attention until it comprises the breath sensations in the entire body. This is a huge amount of sensory data, and keeping your attention on it all at once stretches your attention so much that no subtle distractions can ‘get in’. Those parts of your mind which were throwing up subtle distractions quiet down and eventually become silent now they don’t have the energy of attention to draw on. When some time has passed without any subtle distractions, move your attention back to the nose and try to maintain exclusive attention on this smaller area. When subtle distractions begin to creep back, repeat the process. Eventually you will be able to sustain exclusive attention on the breath sensations at the nose for longer and longer periods of time. This is a truly extraordinary ability; you are able to place your attention on a simple meditation object, and hold it there for long periods of time at will with such a degree of attentional control that no mental images, thoughts, or other body sensations intrude. I have given a brief and dry description of the process, but this can be an extraordinarily peaceful and joyful state to inhabit. However, it is unlikely to come quickly. Continued engagement with the process is required. One huge benefit of deliberate practice is that, since it’s the fastest way to see progress, eventually the satisfaction of seeing that progress becomes its own motivation. It is rewarding to be able to perform a highly skilled task successfully. I maintain that if people can happily devote their lives to learning how to hit a small white ball into a hole, then anything can become intrinsically rewarding. Of course, meditation has the added advantage that it reliably enables altered states of consciousness, which can be extraordinary and blissful to explore. Furthermore, skill in meditation can feed very clearly and directly into the reduction of suffering in daily life. It can help one to gain extraordinarily liberating insights into the nature of the mind, and into how our suffering is constructed. It has many more “mundane” benefits as well, which can feed readily into your motivation to continue engaging in the practice. If you keep practicing, you will benefit from less reactivity and stress, more calm, greater ability to focus, more joy, happiness, all-around better mental health and less predisposition to anxiety and depression, greater empathy, greater self-control, better cognitive flexibility and working memory, and a whole host of other benefits for your brain, and general health. Remind yourself of these. Read or dip into research, poetry, meditation literature, online forums, Buddhist sutras, or whatever else you find inspiring. It is important not to wait until you have reached some arbitrary stage to begin enjoying your practice. There will always be pleasurable experiences available. It may be the joy of a quiet mind, the cool tingle of an in-breath, or even the small success that comes every time you notice a distraction. These pleasures may be simple, but don’t let them pass you by unsavoured. Not only is the cultivation of joy and contentment a crucial sub-skill of meditation itself, but fully enjoying your practice will be of immense help in providing the motivation to continue it every day. Join a community. Finding a group of like-minded meditators with whom to discuss practice and get support is enormously motivating. Not only is the social contact and support good for your mental health, but their passion will be infectious, and you will learn much from group discussions and hearing about the practice of others. Get a teacher. A teacher will be able to provide feedback on aspects of your practice that it would have taken you a long time to figure out by yourself. Teachers can also provide motivation and support when you need it, and help you to get over dispiriting plateaus in practice faster. With all this said, I think the most important factor in continuing engagement is simply to build a meditation habit. Get a routine you can follow every day and stick to it. Make time, and you will make progress. |

A TL;DR Summary of Deliberate Practice:

- A developed enough field is required for one to benefit from the work done by our forerunners to figure out a detailed map of the mental representations that are required for the performance of a skill, and a set of practices to develop those representations.

- Don’t try and practice every element of the skill at once. Rather, break the skill into highly specific sub-skills. Of these, identify one or two of the most fundamental that are holding your skill back. Work on those.

- Ensure that you have a good source of immediate feedback, and adjust your efforts accordingly.

- Fully engage with the challenges of the practice you’re working on. Don’t let yourself slip into autopilot.

- Get outside your comfort zone – try to do something that you can’t already do. The task should be challenging enough that full mental engagement is just enough to learn from the positive feedback – so that the feedback you’re getting is neither all positive (meaning the task is too easy for your current skill level) nor overwhelmingly negative (meaning the task is too challenging for your current skill level).

- Continue practicing. Find what motivates you and savour the fruits of skilled meditation practice.

Thank you for this post. For the past year of my 3-year daily practice I’ve experienced a feeling of stagnation and a loss of curiosity and engagement, to the point of missing days here and there. Meditation had begun to feel mechanical and boring. This guidance, especially changing the object of meditation has presented a new challenge. Noticing a smaller blip of a distraction is somehow easier when focusing on something I’m not used to. Thanks for helping me re-engage.

Regards,

Matt

Tx you for this Kindest Regards Eve ❤

This is how I do meditation for the last 3 years. Before was just breathing or listening to nice audios.

Today when I say I need to mediate it means I’m going somewhere while I’m in this place. See you all soon.

Consider reading Mastering the Core Teachings of the Buddha, Daniel M. Ingram. I found it very useful to deepen practice.

Jonathan

This is fantastic and I foresee sharing this post broadly.

One thing I note is that open awareness, do-nothing, etc style is mentioned as potentially useful but not a primary practice. However, several prominent teachers such as Shinzen Young, Adyashanti, and others promote such practices as very important or central. Shinzen says that if he could only teach one technique it would be ‘note gone.’ The way that I contextualize this is by splitting practice into 3 primary types the same way as is done traditionally (samadhi, panna, sila) to which I refer as concentration practice (the kind under discussion in this post, and most amenable to deliberate practice), insight practice(which include open awareness, note gone, and other such practices as means of gaining such insight), and integration practices (anything that bridges the skills gained in the former two to more skillful ways of being in the world). My read is that according to the Buddha, concentration is mainly useful for putting us in an ideal state to practice insight. Concentration can reduce suffering in the moment, but is still reliant on causes and conditions (the specific causes and conditions that allow practice of concentration) to work and thus do not represent full freedom. Such concentration focused schools of thought already existed at the time of the Buddha.

This was awesome. Thank you for taking the time to write it.

Interesting post. As someone who does not follow the TMI approach, I disagree with these suggestions. Samatha (and probably meditation in general) is more of an art than a science. This is why the basic instructions are so simple. It is important for meditators to “play” with the breath and the perception of the breath in order to create a sense of relaxation, calm and tranquility. In fact, Samatha is probably better translated as “calm and tranquility”, rather than as “concentration”. The effort exerted should be minimal, just enough to sit upright and focus on the meditation object. This contrasts with TMI’s (and your) suggestions of giving yourself constant feedback, focusing on skills and sub-skills, and so on. It seems to place too much emphasis on striving. Maybe this could help beginners make quick progress at early stages, but I feel like this kind of striving would be a roadblock at deeper levels of concentration.

“The effort exerted should be minimal” – I totally agree that in meditation effort need only be very light. But it should be effort in the right direction, and that takes some strategising and careful observation of how your practice is going.

“I feel like this kind of striving would be a roadblock at deeper levels of concentration” – Again, I totally agree. If you read TMI, the later stages point out that even the light effort required in the early stages I’ve covered here eventually get in the way and you need to learn to let go of effort completely 🙂

I have to thank you for this post since it was able to get me out of my meditation rut.

I have been searching for the missing piece of the puzzle on how to make consistent progress in meditation, but most teachers tell you to just continue what you are doing. Somehow, that has never been a satisfying answer for me.

I also have been looking into deliberate practice lately, but did not know how to combine both (although it was clear to me that this was the way to go).

So this article spares me the tedious task of combining them myself (for which I am very grateful).

I’m also grateful for the link to the book by Culadasa. I already got a copy and I will study it in detail, hoping to finally getting to the next stage!

After TMI, this is the best source of information on meditation that can be found. Great job, keep writing more.

Thanks for the kind words! 🙂

Great post! Beginner here, only at stage 2, but I love the science based approach. I appreciate that you’re willing to fight the narrative of simple meditation techniques/”just do it” mentality to encourage an optimal practice.

I wish you wrote your notes for stage 7 to stage 10.. I am somewhere at stage 5-6 and want to accelerate progresw